'It's an artwork from beginning to end:' Body, Art, Noise, and Fluxus in the Work of COUM Transmissions/Throbbing Gristle

Performance art prompts the unique development of a kinaesthetic relationship between artist and audience through the dynamic implementation of the body. Where ‘static’ art is removed from the artists’ body through the process of display, performance art allows for direct physical interaction between the artist, their work, and the viewer. This interrelation was explored extensively in the works of Fluxus and COUM Transmissions/Throbbing Gristle. These two collectives emerged from shared principles of using live events, the body, the construction of an art-focused lifestyle, and sound as instigators for sensual exploration and engagement. COUM/Throbbing Gristle expanded upon Fluxus’ developments in experimental ‘intermedia’ performance art by integrating static visual work with live industrial noise music demonstrations. Both COUM/Throbbing Gristle and Fluxus utilised an interconnected process of sonic and visual stimulation to explore the actualities of pain, pleasure, and repulsion.

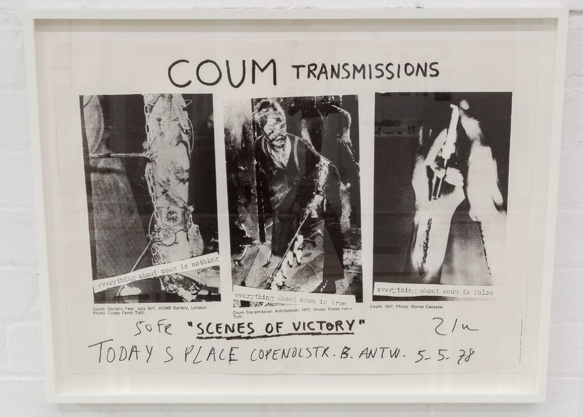

COUM Transmissions emerged from the working-class city of Kingston-Upon-Hull, England, in 1969. The collective was formed by Genesis P-Orridge (1950-2020), Cosey Fanni Tutti (1951--), Spydeee Gasmantell, John Shapeero. Taking inspiration from performance artists Jospeh Beuys (1921-1986) and Allan Kaprow (1927-2006), the collective praticed guerrilla street theatre.2 Dressed in absurdist homemade costumes, they employed props, singing, and poetry to engage members of Hull's public in joyful theatrical demonstrations.3 In addition to performing together, the group also lived communally; sharing clothing, beds, and meals with each other while squatting an abandoned warehouse. This lifestyle allowed COUM to focus solely on each other and their practice, which extended their group performances into a "total art" experience.4 This same sentiment was expressed by Fluxus figurehead George Maciunas (1931-1978), who, in an early 1960s letter proclaimed: "Fluxus should become a way of life, not a profession."5 Through this framework, the intention behind artistic creation and the shaping of lifestyle become inseparable: a symbiotic, and sometimes parasitic, relationship between body and practice.

This dissolution of the boundaries between artistry and lifestyle ignited a turbulent co-dependency between P-Orridge and Tutti as the group's line-up haemorrhaged. While maintaining their anti-collegiate, do-it-yourself attitude, COUM's performances shifted from light-hearted street theatre to "darker and more experimental styles… performance art that involved body modification, ritual scarring, immersion in various bodily fluids, [and] sodomy."6 In one such event, P-Orridge, who had binge drunk whiskey and consumed poisonous twigs, carved a swastika-turned-Union Jack into h/er chest with a rusty nail; resulting in a "rush to the University hospital… by the time I got there they couldn’t find a pulse."7 By tapping into these extreme forms of publicly displayed, self-inflicted violence, COUM was reimagining their previous tenets of comic absurdity and surprise into a darkly physical performance. The shock of their audience became a competition, as they sought to push both "their bodies to the limit and test the audience's capacity for disgust."8 Tutti also began to model for commerical pornographic magazines – an artistic "self-sexual exploration,"9 that would come to define her independent photographic practice. Through self-mortification and displays of self-sexuality, the group encouraged their audience to reconsider the lines between pain, pleasure, entertainment, and revulsion.

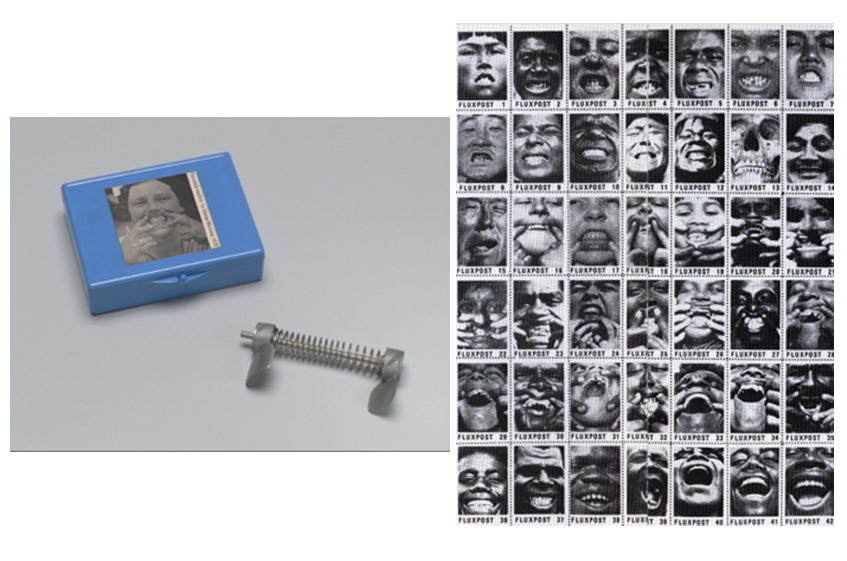

Around the same time, Fluxus figurehead George Maciunas was exploring his own relationship to violence through the works Flux-Smile Machine (1970) and Fluxpost (Smile Stamps) (1978). Flux-Smile Machine, reminiscent of medieval torture devices, is a spring-locked metal contraption that forces the wearer's mouth into a painful 'grin.' Through this device, Maciunas is subverting the typical positive emotions of a smile into an expression of discomfort. He carries on these themes in Smile Stamps, a photolithograph consisting of a six-by-seven grid of stamps that had accompanied the mail-order Smile Machines.10The stamps are emblazoned with images of individuals showing off abnormal dental pathology with open mouths. Each person displays a different expression, ranging from toothy grins to deep frowns. In some stamps, an individual's hands pull violently at the skin of the subject, provocatively exposing the teeth to the audience by antagonistic force - a corporeal externalisation of the Flux-Smile Machine. Friend of Maciunas Barbara Moore describes his relationship to this piece in her article "Finger in Fluxus," stating: "he acquired an attraction for pain so intense that he enjoyed flagellation… soon after he designed the Smile Stamps, he openly told friends that 'the pain kills the pain.' Whatever private obsessions had been sublimated into his work and imagery, his pleasure had finally become public."11 Through these works, Maciunas becomes an instigator of pain. Either directly as through the Flux-Smile Machine or indirectly as through the presentation of disturbing imagery in Smile Stamps, Maciunas is exerting dominance over his audience through carnal displeasure.

COUM Transmissions participated in this same form of subjugated artist-on-audience violence through the integration of musical elements into their practice. Moving to London in 1973 broadened the group's reach, attracting photographer Peter "Sleazy" Christopherson and sound engineers John Lacey and Chris Carter to the group. The latter brought expertise on the building and use of custom synthesizers that would become fundamental to the formulation of Throbbing Gristle.12 P-Orridge, Christopherson, and Tutti, had "gotten bored with everyone thinking what [they] were doing was art, so [they] decided to spoil it by doing whatever else [they] were worst at, and just did the music."13 The final COUM 'transmission' was a 1976 exhibition titled "Prostitution," held at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. Like Fluxus' Internationale Festspiele Neuster Musik in 1962, COUM Transmissions integrated music, visual art, and performance into a dynamic event.14 However, instead of John Cage, Yoko Ono, George Brecht, and a destroyed piano; performers at "Prostitution" included a stripper, a comedian who "told dirty jokes,"15 and COUM Transmissions -- now Throbbing Gristle -- positioned against a background of bloodied tampon sculptures (Tampax Romana) and a collection of Tutti's adult magazines, which could only be accessed by paying a legally-required fee.16

Throbbing Gristle's set, known as Music from the Death Factory, opened with harsh, screaming walls of synthesized noise - sonically-adjacent to fingernails on a chalkboard - which melted into distorted guitars, played with no clear resolution in mind. The performance eventually escalated into a "fistfight,"17 with Gristle's unsettling audioscape launching a violent assault, both sonically and physically, onto the installation's patrons. From then on, COUM performed only as Throbbing Gristle, channelling their fascinations with dominance, repulsion, sexuality, and force through electronic music performance. Three-fourths of the group coming from a non-musical background yielded an instinctive form of artistic experimentation unbound by traditional musical tenets. This exploration, aided by Carter's customised electronic equipment, allowed Throbbing Gristle to craft a revolutionary form of artistic practice and performance that transcended traditional notions of how a concert could be experienced.

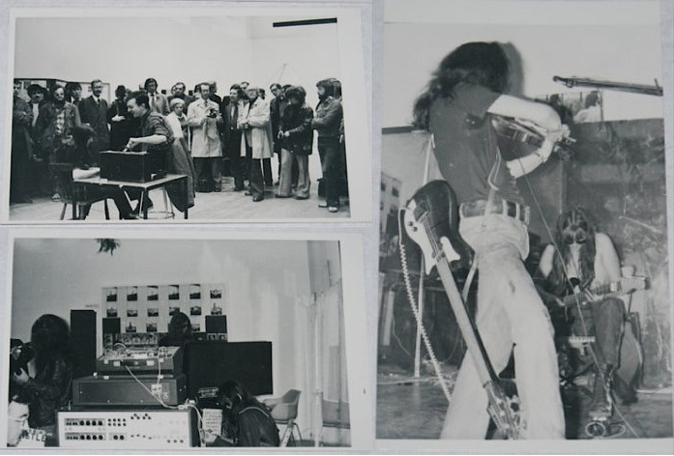

One Fluxus work that complements Throbbing Gristle's multimedia practice is Nam June Paik's TV Cello. This 1971 work was a collaboration between Paik (1932-2006) and the cellist Charlotte Moorman (1933-1991), with the pair producing four works together between 1969 and 1971.18 TV Cello consists of three CRT TV chassis mounted inside clear plexiglass boxes. This allows the audience to observe the complex circuit boards and interior wiring typically hidden by an opaque body, prompting a sense of observing something unclothed. Attached to the top is a simple plexiglass neck that lacks the scroll-like ornamentation of a traditional cello. Four strings cross the faces of the screens and unite into a standard black cello tailpiece. When turned on, the television screens displayed both pre-recorded and live footage of Moorman playing the instrument alongside a "video montage of other cellists and a live feed of a television channel on air."19 The piece, however, takes on an entirely new meaning through the process of Moorman's performance. She emphasises the inherent physicality of cello-playing, drawing out long strokes of the bow against string, with the slide of her hands against the neck. About halfway through the performance Moorman abandons her bow, taking to slapping the instrument's neck with a rhythmic percussion that reverberates through the machine's synthesizer. Her body, save for her bare arms, neck and head, is almost completely obscured by the TV Cello itself, allowing for a sensual amalgamation between player and instrument.20 The cello's synthesized sounds are a deep, rattling timbre, creating a disorienting soundscape. Moorman's performance of TV Cello evokes an cybersynthesis of the body and the machine working in tandem, feeding off each other to produce noise.

Paik and Moorman's conceptualisation of a symbiotic reliance between body and machine is fundamental to Throbbing Gristle's practice of noise performance. The synthesizer (or guitar, bass, lap steel, or microphone) becomes a tactile extension of the performer's body, "blurring the object-subject distinction."21 The transference of noise from player to instrument to audience extends this principle, allowing sound to become an active sensorial agent. A hallmark of Throbbing Gristle's performances, as well as noise music as a genre, is the deafening volume at which the music is played. This is in direct opposition to Fluxus artist John Cage's 1952 performance piece 4'33". Performed in three sections of unequal length, Cage's composition instructs the performer to sit down, prepare their instrument, and not play.22 The performer's silence, therefore, creates noise, as a listener must adjust to the sonic minutiae of their surroundings. The work acts "not as a negation of music but an affirmation of its presence,"23 calling upon the audience to notice non-intentional sounds. Where the performed silence of 4'33" invites the audience to hear their surroundings, live noise music does the inverse: it draws the audience into the sounds themselves, creating an all-encompassing environment of sheer noise. Speaking on live performances by the Japanese harsh noise musician Merzbow, who plays at volumes past the point of safe listening,24 author Greg Hainge describes how "one is sometimes made to attend to these physical properties via pain or even nausea, as sub-frequencies act directly on the audience's internal organs."25 The combination of these loud volumes and the "confronting, harsh, chaotic… and menacing,"26 nature of Throbbing Gristle's sound develops an overwhelming assault on their audience. Sound becomes a physical channelling of gestural violence – a lineage that extends COUM Transmissions' prior investigations of the artist's body as a perpetrator of disgust into a new sonic realm.

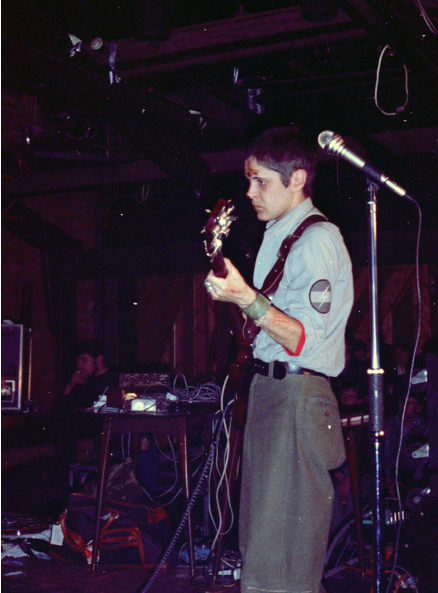

In addition to volume and tone, Throbbing Gristle employed unsettling lyrical and visual content in their performances to try and repulse their audience. During concerts, the band would project footage of "violence, warfare, and pornography,"27 often featuring Nazi concentration camps and extreme bondage. The subject matter of this footage was echoed in the band's regimented visual aesthetic as they donned S.S.-inspired armbands (fig. 6) and festishwear.28 Their cassette tapes and vinyl records were plastered with images of gore and pornography. This use of fascistic and sexualised imagery affirms the band’s intended position as a dominator who forces their audience into submission through visual, sonic, and physical violence. Coercive violence is examined through a sexual lens in the song "Persuasion," off Throbbing Gristle's 1979 album 20 Jazz Funk Greats. The six-and-a-half-minute track chronicles a story of sexual exploitation between a photographer and their model, implied to be a young girl. Powered by a pulsating bassline and dripping with layers of distortion, P-Orridge's horrifyingly austere vocals are intermingled with audio clips of pained screams, cries, and giggles channelled through a custom Walkman-based sampler.29 Through the song's first person pronouns – "Like always, I persuade you / Look in my eye / Under your covers I touch you / And tell you what to do"30– P-Orridge embodies the experience of the 'persuader,' victimising the audience through the lyrical content and sonic harshness of the song.

Both COUM Transmissions/Throbbing Gristle and Fluxus aimed to subvert traditional artistic institutions through experimentation and provocation. They worked to explore the role in which the senses can be provoked through the artmaking process, and how these sensations change due to presented form, media, and nature of its subject matter. Central to these collectives was an investigation into lifestyle, sound, and the human body as artistic mediums. These facets were manipulated and reshaped by the artist to inspire intense emotion and physical reaction from an audience, which is most vividly experienced through a live setting. Whether in an art gallery, concert hall, or street performance, and facilitated through sound, theatre, or visual media, COUM Transmissions/Throbbing Gristle and Fluxus constructed an expansive environment of audio-visual ferocity, blurring the boundaries between control, liberation, discomfort, and pleasure.

Written October, 2023.

Bibliography:

"Charlotte Moorman Performs with Paik's 'TV Cello.'" YouTube, May 4, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-9lnbIGHzUM&ab_channel=ArtGalleryofNSW.

"Charlotte Moorman with TV Cello and TV Eyeglasses." Nam June Paik: The Future is Now. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://explore.namjunepaik.sg/artwork-archival-highlights/charlotte-moorman-with-tv-cello-and-tv-eyeglasses/.

Cogan, Brian. "The Last Report: Throbbing Gristle and Audio Extremes." Essay. In Hardcore, Punk, and Other Junk: Aggressive Sounds in Contemporary Music, edited by Eric Abbey and Colin Helb, 107–20. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Plymouth Books, 2014.

Cogan, Brian. "'Do They Owe Us a Living? Of Course They Do!' Crass, Throbbing Gristle, and Anarchy and Radicalism in Early English Punk Rock." Journal for the Study of Radicalism Vol. 1, no. 2 (Summer 2007): 77–90. Published by the Michigan State University Press.

Conte, Lisa, Christine Frohnert, Lisa Nelson, and Julia Sybalsky. "Overcoming Obsolescence: The Examination, Documentation, and Preservation of Nam June Paik's TV Cello." The Electronic Media Review Vol. 2 (2013). https://resources.culturalheritage.org/emg-review/volume-two-2011-2012/conte/.

Friedl, Reinhold. "Some Sadomasochistic Aspects of Musical Pleasure." Leonardo Music Journal 12, no. Pleasure (2002): 29–30. https://doi.org/10.1162/096112102762295098.

Hagen, Ross. "No Fun: Noise Music, Avant-Garde Aggression, and Sonic Punishment." Essay. In Hardcore, Punk, and Other Junk: Aggressive Sounds in Contemporary Music, edited by Eric James Abbey and Colin Helb, 91–106. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Plymouth Books, 2014.

Hainge, Greg. Noise Matters: Towards an Ontology of Noise. New York, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum. "Fluxpost (Smiles)." Harvard Art Museums. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/237506.

Hed, Marcus Werner and Dan Fox, Other, Like Me. Genesis P-Orridge, Cosey Fanni Tutti, Peter Christopherson, Chris Carter. 2020; United Kingdom: BBC TV. https://archive.org/details/OtherLikeMe.

Kouvaras, Linda. Loading the Silence: Australian Sound Art in the Post-digital Age. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, 2013.

Kromhout, Melle Jan. "'Over the Ruined Factory There’s a Funny Noise’: Throbbing Gristle and the Mediatized Roots of Noise in/as Music." Popular Music and Society Vol. 34, no. 1 (February 10, 2011): 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2011.539814.

"Leaflet for the Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester..." Nam June Paik: The Future is Now. Accessed October 14, 2023. https://explore.namjunepaik.sg/artwork-archival-highlights/leaflet-for-the-fluxus-internationale-festspiele-neuester-musik/.

Moore, Barbara. "George Maciunas: A Finger in Fluxus." Artforum Vol. 21, no. 2, October 1982.

Nyman, Michael. Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. Seconded. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Phillpot, Clive. "Manifesto I. Fluxus: Magazines, Manifestos, Multum in Parvo." George Maciunas Foundation Inc., February 13, 2013. https://georgemaciunas.com/about/cv/manifesto-i/.

Tutti, Cosey Fanni, Genesis P-Orridge, Peter Christopherson, and Chris Carter. "Persuasion." Genius. Accessed October 11, 2023. https://genius.com/Throbbing-gristle-persuasion-lyrics.

"TV Cello, 1976 by Nam June Paik." Art Gallery of NSW. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/343.2011.a-c/#bibliography.