Anonymity in Cyberspace: Born-Digital Gender and Perceived Authenticity in Dennis Cooper's 'The Sluts' (2004) and Annie Abrahams' 'I only have my name?' (1999)

This is a transcription of a radio broadcast I wrote for Dublin Digital Radio's 'Queering the Airwaves' series, June 2025. Here is the archived broadcast.

.jpg)

How do we appear to others when no one can see, hear, taste, or smell us? As Andrea Long Chu puts it in her 2019 novel 'Females,' "gender is something other people have to give you."1 Sensorial perception is a major part of how we see the identities of those who we engage with. This method of perception is upended, however, when face-to-face communication becomes screen-to-screen. The proliferation of the digital into the physical world has innumerably changed the process of self-expression online. With services like LinkedIn and Facebook dominating the 'professionalised' Internet, users feel increasingly pressured to present an 'authentic' version of the physical self in the digital realm as these lines between on and off-line begin to blur.

What does striving towards this online authenticity mean for a queer person? How our narratives are spoken drastically differ in language depending on who they are being spoken to, due to internal and external pressures. Communicating online allows one to omit or include the body in this process, transcending the physical traits it may feel impossible to obscure in face-to-face interaction. Speaking from a trans perspective, this can feel as if it presents a 'truer' more 'internal' self, where thoughts are communicated without corporeal pressure.

Where this digital self-construction can be used as a means to present an 'authentic' self, it also enables veracity to be discarded or made obscure. When you reject this pressure towards a cishetero cyber-genuineness, using the Internet opens opportunities for play and transformation through the crafting of a queer digital self. The formulation and performance of an anonymised identity online is made possible by entirely untethering the physical body from the digital self. The easiest way to do this is through text-based communication. On the early Internet, where text was this primary language, forums and webrings acted as hubs for queer counter-cultural sexual expression. They presented the option for authenticity, but also for falsehood, exaggeration, and ambiguity of self.

I'm your host, Francis, and you are welcome to "Anonymity in Cyberspace: Born-Digital Gender and Perceived Authenticity in Dennis Cooper's 'The Sluts' (2004) and Annie Abrahams' 'I only have my name?' (1999)." For the next thirty minutes, I'll be leading you through two twisting cybernetic narratives that consider the construction of queer anonymities and fabricated identities in the virtual realm. We will be exploring the intersections of truth and falsehood as a fundamental part of making a digital queer identity, and see how those two supposedly incompatible states of being coalesce online.

'The Sluts' is an epistolatory novel that was published by the prolific gay American author Dennis Cooper in 2004. Cooper's literary output began in 1978 with his punk zine Little Caesar, and over time would expand to include fictional and autobiographical literary works; including novels, poetry, plays, films, and his infamous multimedia WordPress blog. The unifying thread throughout Cooper's work is his exploration of the relationship between violence and desire. His work oozes with corporeality - no matter the medium, you are never too far from engaging with the most intimate, interior acts of how the body functions, and how those functions can be willingly or unwillingly undone.

The narrative of 'The Sluts' unfolds through a series of posts on a gay men's escort website; through emails, message boards, chatrooms, and transcribed phone calls. The plot of the novel is astonishingly convoluted. The story swirls through modes of truth, between outright lies, partial lies, and ideas unconfirmed. Each bit of information that the reader begins to believe is true is later decried to be at least partially fabricated. It feels impossible to keep each story straight. The hectic and constant back-and-forth of the story's structure is contingent on its mode of operation as being told through online posts. The dissemination of information online is both instantaneous and uncontrollable - a facet of Internet usage that is brilliantly captured by 'The Sluts'' fast pacing.

The novel's timeline begins in June of 2001 and ends in May of 2002. It opens with a review on a gay men's escort forum advertising the "unbelievable" talents of a masochistic young sex worker named Brad, who works out of a bar called Pumper's in Long Beach, California. Two reviews later, Brad is described by a user named JoseR72 as having undergone a mental health crisis and having entered outpatient treatment. Brad responds by stating: "Don't believe this guy, he's a prick… he's a liar. I'm writing this on his computer. What does that tell you?"2

This will be the only time that Brad actually speaks as Brad. In review number 5, Cooper introduces Brian, who posits that Brad is suffering from the effects of a brain tumour. Brian goes on to become Brad's spokesperson on the forum, stating that the two had entered a relationship while he encouraging Brad to seek new clients. Each new client review of Brad becomes more salacious and graphic than the last, ranging from the purely sexual to the homicidal. This fire is stoked by Brian, who responds to each client review to either verify it as truthful or claim it as an outright lie.

These exchanges begin to attract a rabid following on the forum. The story becomes increasingly complicated as other local sex workers are drawn into the textual fold, and as Brad travels between California and Portland, Oregon. As the reviews steadily become more graphic, so does the insistence of the posters that they are true. It is consistent throughout these reviews of Brad that those who post them do so to advertise their own services as sex workers or their availability for sexual intimacy outside of their profession. The sexual skills of the posters, their attractiveness, their proximity to Brad, are all exaggerated as an act of marketing. This process affirms the purpose of the website itself: selling sex. This form of autopornification especially lends itself to the sadomasochistic dynamics in the reviews, where the reviewers dominate Brad not only physically and sexually, but narratively, through the crafting of fantasy.

The person tasked with verifying and uploading these reviews is the Webmaster. They are only referred to as their title and are never given a first name. It is unknown whether the Webmaster is one person or multiple, which adds to their intrigue as a character. The webmaster acts as an omniscient-but-not-really narrator - they have access to all of the reviews that get submitted and subsequently controls the overall narrative by choosing which to publish. Early in the novel, they say that they "will try to separate the fact from the fiction, if there are any facts to be found."3 This is an admission of fantasy. The webmaster acknowledges the fictionalised nature of many reviews, and yet is committed to presenting them as if they are authentic; adding to their intrigue.

In chapter three of the novel, the Webmaster opens up a discussion board, and briefly steps away from their role as truthkeeper. During this section, a forum user named boybandluvXXX, whose ultimate fantasy is to torture and kill Nick Carter of the Backstreet Boys, sets up an alternative discussion group, appropriately named Kill Nick Carter. Unlike the Brad and Brian reviews, the Kill Nick Carter fantasies are comically outlandish - there's one where a naked Nick is thrown into a lion's cage. The Kill Nick Carter forum acts as a foil to the reviews of Brad and Brian due to the disclosure as pure fantasy, or as boybandluvrXXX puts it, "a sick porn." They don’t try to be true in the same way the Brad and Brian reviews do, and thus their moderator approaches them in an entirely different manner.

The Webmaster for Brad and Brian's saga takes their role incredibly seriously, stating that they contact all reviewers by email or phone call for verification. The thread that binds all of the Brad and Brian reviews is this act of verification as they search for one truth: Who really is Brad? And who is Brian?

The character of Brian is constructed ambiguously. He is introduced as Brian. Quickly, Brian is believed to be the pseudonym of an adult film actor named Stevie Sexed. Once Stevie is found dead, this character of Brian continues posting. One forum user named thestinge believes that the "real" Brian was operating under several screennames. Brian does not seem to be able to keep his own truth together: where he will say a review is truthful, he will then double back, and say he was lying about it being truthful. Brian's position as speaking for Brad should hypothetically imbue his writing with an authority and truthfulness, but his haphazard intercessions between fact and fiction make this impossible.

The identities projected onto Brad, however, seem more concrete. They range from another Californian sex worker named Kevin to a Brian Gordon, a man who served time in prison after committing arson on a Portland-based construction business. This business is owned by a forum user named builtlikeatruck44, who wrote a review of Brad described by the site's Webmaster as "our first legitimate review on Brad in some time."4 In the final chapter of the book, Brad becomes another sex-worker and forum superfan named Thad. It is revealed that a series of emails and faxes from Chapter 4 that were presented as being sent between Brad and Brian were actually sent by Thad, who was pretending to be Brad.

Thad believed he was speaking to the real Brian, but he was actually speaking to Zack Young, a man who was pretending to be Brian. Zack had also been active on the forum pretending to be a journalist who was writing about the Brian/Brad saga under the screenname thegayjournalist. A "high level software designer at IBM,"5 Zack had the capabilities to "mastermind" the forum thread, and did so using at least two screen names. A review from a supposed previous lover posits that Zack, though "he’s gorgeous and the best top I’ve ever tricked with in my life,"6 was a serial liar and forum obsessee.

However, Zack did believe that he was speaking to the real Brad. He states that he "didn't know or at least wouldn't let himself believe that his Brad wasn't the real Brad… Brad's history is built on myths and lies, some of which I admit to perpetrating myself."7 Zack and Thad both believed that the other is the True Brian and Brad, allowing them to become a simulacra of the initial Brian and Brad. This ruse is only discovered when their new clients post photos of "their" Brad, and Brad's old clients from the beginning of the novel claim him to be an entirely different man. Zack, the forum's readers, and the novel's readers have all been duped.

The true identities of Brian and Brad are unimportant when they exist within the realm of fantasy. The draw of discovering who they truly are, of giving them names and wives and scorned ex-lovers, feeds into their mythologisation. Brad and Brian become cyborgs, a state of being described by Donna Haraway in her 1985 essay 'A Manifesto for Cyborgs' as "a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction… a condensed image of both imagination and material reality."8 Their only proven existence is on the computer - their machine - but the mystique of their story is built by tracing their existence as organisms in the real world. But the Brad and Brian presented on the forum are not the living Brad and Brian: they exist as a cyborg product of communal digital imagination. Their existence is contingent on their being online, and being perceived by the forum's users.

Where this fantasy begins to slip is when the corporeal interacts too closely with the digital. The projection of the digital identity on the physical body breaks the sanctity of online anonymity. In the third chapter of 'The Sluts,' while Brad Gordon is in prison, people acting as his wife Elaine publish his mailing address. Forum readers are encouraged to send Brad mail for a donation fee of $100. Builtlikeatruck44, whose business was burnt down by this Brad, states that forum users "should fantasize about anything you want, but don't write him letters and lay your shit on him. That's where it gets amoral."9 The act of sending a letter forces the virtual Brad to become the physical Brad. In the final chapter of the book, where Thad and Zack become Brad and Brian, the forums' followers gradually become less interested in the saga. A long-time user named snazzystocky makes a post that reads: "Is it just me, or has the fun and eroticism gone out of this Brad thing?... as far as I can tell, these reviewers are actually doing these things to him and not just making up evil fantasies about him and pretending they're true… I feel really disappointed."10 Though fantasies of physical violence had been present in the saga since its onset, the introduction of geographical photographic identification causes the veil of fiction to dissolve. The psychosexual pleasure of digital violence, when forcefully exerted on a physical body, becomes unpleasurable due to this physicality.

The answers to the questions Who is Brad? And who is Brian? Depend on what you're seeking from each character. In one of the final reviews in the novel, Zack, posing as Brian, states: "Of course I knew Brad, and you didn't. Brad was just your idea, and I guess you think he's a great idea, but Brad himself is just a kid who got drafted into a job of representing an idea. Now Brad is just a name. You don’t even know who it belongs to anymore. The point is, this is your story and your ending, not Brad's and mine."11

Annie Abrahams is a Dutch cyber-feminist Internet artist born in 1954. Abrahams has traced her artistic production to her doctoral degree in biology, which stoked her interest in the communications systems constructed by living organisms. She used her first computer in 1991 and integrated it into her artmaking practice in 1996. As an artist, Abrahams' work coalesces the digital and physical into what she calls "networked performance art." Like Cooper, Abrahams uses the Internet as a medium to both prompt and record instances of textual communication that are dependent on this digital format. In an interview with Evelin Stermitz from Hz Journal, Abrahams describes the early Internet as "a public space of solitude. A place where one isn’t meeting the other person, but the image one makes of this other in one's imagination. One contemplates the other in one self."12

Abrahams explores the interactions between these others and selves in cyberspace through her series of works titled 'Being Human.' Spanning between 1997 and 2008, these works "concentrate on the possibilities and limitations of communication on the net," by using "the internet as an artistic medium that permits addressing people in their own intimacy."13 Many of the works, like 'don't touch me / ne me touchez pas' and 'understanding/comprende,' are presented both in French and in English, which questions the role of spoken and written language in digital modes of communication.

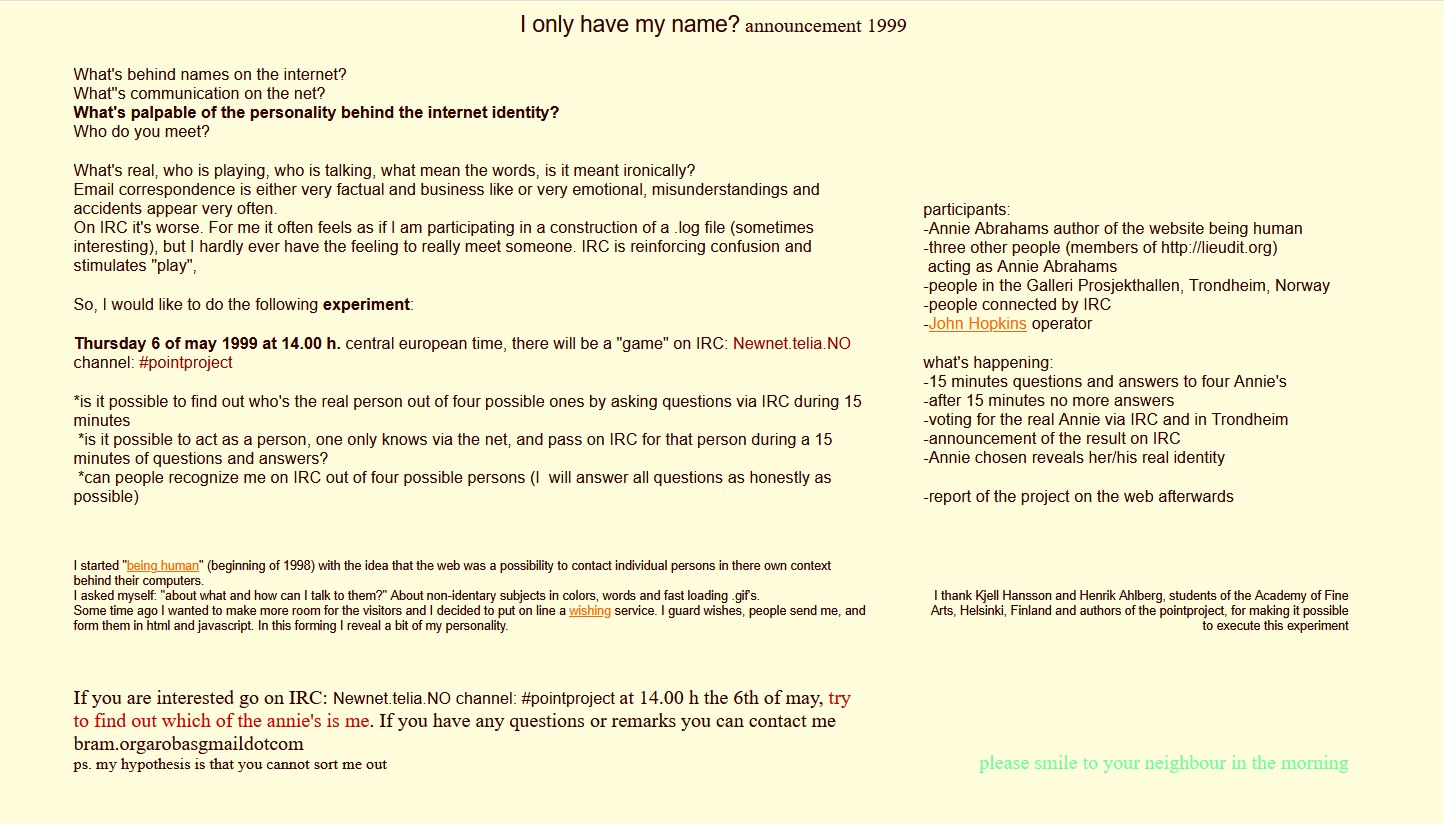

Abrahams explores the themes of constructed identities and online anonymity most pertinently in her work 'I only have my name.' The piece exists today as a colour coded .log file captured from IRC, or Internet Relay Chat. Like 'The Sluts,' the work exists without imagery, which allows the text to be upheld as the primary form of engagement both between the speakers and the viewers. The work was mostly completed in one evening.

On Thursday, the 6th of May 1999, Abrahams conducted an experiment on the text-based Internet Relay Chat forum Newnet. She formulated this experiment around three questions:

1. Is it possible to find out who's the real person out of four possible ones by asking questions via IRC?

2. Is it possible to act as a person, one only knows via the net, and pass on IRC for that person during 15 minutes of questions and answers?

3. Can people recognise me on IRC out of four possible persons? (I will answer all questions as honestly as possible).

To solve these, Abrahams set up four users on IRC chat: anniea, annieb, anniec, and annied. The other Annies were played by Pierre Cuvelier, Karen Dermineur, and Yann Le Guennec, with John Hopkins acting as chat facilitator. She organised 15 minute question and answer sessions and tasked other users on the IRC, most of whom were students at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki, Finland, to discover which of these four Annies was the "real" Annie Abrahams.

The chat record begins with simple introductions, determining names and places of origin. One chat user called kuva is in Norway, projecting the project on a wall, while annied speaks from a bar and anniec speaks from her home. When all Annies are present, they speak:

Anniea: hello everyannie

Anniec: we are complete

Anniec: all one

The Annies, at first, intend to operate from a point of inseperability. Despite the different initials in their names, they are all acting together as Annie.

Frutja asked: so all annies tell me please who you are?

Anniea: you have to prove it

Anniec: I am annie

Annieb: all annie are annies

Then, a user named LuciferFr asks:

So, annieb, tell me about your first sexual experience with another women.

Annieb responds: ask my mother

Anniea: never had such an experience....

Annied: please no personal question

Jaceeee: but I remember you telling me something like that, anniea

Annieb: that one was not personal, was it?

So quickly, within the first four minutes of the experiment, does the conversation delve into a sexual realm. It is the intimacy of sexuality that spurs this attempted act of identification. Read through a queer lens, it seems as an act of outing – if there was a sense of shame, responding to the question may cause a falter in confidence that could point to the Real Annie. A sexual experience as being two-sided also causes one to encounter the subjectivity and identity of another person, whose testament could provide evidence of the Real Annie's identity. Where Annieb responds "ask my mother," she minimises the impact of the question by subverting it through a humorous lens. Though written in 1999, it still feels like a conversation being had in 2025; you can feel the sense of deflection and the awkward silence between answers despite not hearing a speaking voice.

As the conversation continues, two more Annies are introduced: anniee and annief. Like Thad and Zack in 'the Sluts,' these two Annies are not present at the narrative's origin, but morph into their roles as Annie over time. The same occurs when the user jaceee becomes Annieg. Though not being the original Annies, they are still Annies. AnnieF, like LuciferFr, acts as sort of an instigator. She approaches the quest towards truthfulness with a sense of hostility, saying that she "doesn't like anniec," which causes jaceee to respond "anniea told me anniec was a bitch." Annief also says outright "I have to tell you I'm not annie," which is swept over in the chat undiscussed. This act of misidentification could potentially be viewed as identification, an act of stepping away from one's self to find one's self. The experiment goes on.

The user LuciferFr asks: When is identity crucial?

Annieb answers: at birth time I suppose

Anniec: when you pass borders

Frutja: isn't it crucial to not have an identity?

Jaceee: the border is birth, birth is the border

Annieb: birth is the first becoming

Jaceee: what about the border of death, anybody checking papers there?

Anniec: I only have my name

A place where identity stops becoming malleable is in legal documentation. It feels here the Annies are referring to birth and death certificates. At birth, you are given your name, and given your assigned sex – the cornerstones of how identity can be perceived by others. Death, a leveller, transverses these qualities. In 'the Sluts,' the only times the identities of characters are verifiable is when they die and their obituaries make local news or when they get charged with a crime. The murdered Stevie Sexed becomes Kenneth Miller, while his killer, known on the forum Corey #3, becomes David Barrows. Documentation represents a formalisation of identity that does not, especially from a trans perspective, encapsulate who you really are, or what people know you as. In 'I only have my name,' there is purposefully no form of identifying documentation – the Annies are Annie because they say they are Annie. It becomes crucial to have an identity, then, when you are trying to relate this identity to others.

How do these identities change in the context of a screenname? Do you remain yourself when your name changes, when that is such a crucial part of perceived identification? As IRC user No_one puts it, "is just taking a name being someone?" In 'The Sluts,' Cooper employs over 75 individual screennames to serve as his cast of characters. The people behind these screennames, however, shift and change: you're never quite sure who is operating as who. Some characters reappear throughout the novel, some change their identity, and others disappear into virtual nothingness. The sheer amount of people to keep track of creates an atmosphere of overwhelm that lends itself perfectly to the novel's setting in cyberspace. In 'I only have my name,' around halfway through the exercise, many of the Annies decide to become Lucifers, saying that "they cannot stay annie for ages." Annief becomes just lucifer, annieg becomes LuciferFt. Jaceee becomes LuciferQ. This redefinition of character reflects the chaos developing within the piece's narrative, as trying to discern identity becomes increasingly difficult.

LuciferFt states: damnit, wat is happening?

LuciferFr responds: I don't think anybody should be annie. Actually, it doesn't matter

The Annies and Lucifers subsequently begin to sign off, feeling it was impossible to discern which Annie is the Real Annie. When annied signs off, it is with the message that this annie was Annie Abrahams. But none of the remaining users seem to care, and they continue chatting on the IRC.

Annier states: I don't know who you are

Anniec responds: YOU? Well, I do know you are part of ME and vice versa

By being Annies, they all became the Real Annie in the eyes of the viewer, even if they weren't being operated by Annie Abrahams herself. Like in 'The Sluts,' it is this aspect of fantasy play that becomes more exhilarating than finding out the actual truth. The pleasure of the mystery, and of watching the construction of identity in real time, supersedes the intention of the original experiment.

So what was the outcome? Annie Abrahams discovered that while it isn't possible to find out who’s the real person out of four possible versions, it is possible to act as another person one only knows via the net. Internet Relay Chat being the medium of this piece allows for this exploration of constructed anonymity, through which one overshadows the self by becoming another. The Internet's veil of disconnecting the physical body from the mind and from spoken language allows for the manufacturing of selfhood solely through text-based channels. Had this experiment taken place within a real-life room, the body and its physical characteristics will always act as a barrier to true anonymity.

It is this digital disconnect between body and personality that makes these narratives so intrinsically queer; particularly genderqueer. The public forums of Cooper's gay escort website and Abraham's IRC server function as places to discover, discuss, and disseminate identity. Necessary to note is the lack of visual imagery in these two examples. The construction and communication of self exists here only within the textual realm, which provides, in my opinion, more opportunities for play and performance of identity than uploading personal pictures does. The sexual nature of many conversations in these two works demonstrates the capacity of these text-based sites to foster the externalisation of intimate desires; desires that may be kept inside in real-life due to shame and stigma. By removing the pressure of speaking through a physical body, it becomes easier to express what that body wants. This is especially important in a queer context. When Dennis Cooper published 'The Sluts' in 2005, sodomy had only been made legal in the United States two years prior, in 2003. The Internet, with its potential for anonymity through the obfuscation or fabrication of identity, gives this act of confessing desire an integral sense of safety. Communicating online allows you to create, become, and express any version of yourself - even a version of yourself that’s not yourself at all.

Bibliography:

Abrahams, Annie. 'Being Human.' 1997-2007. https://www.bram.org/

Abrahams, Annie. 'I only have my name?' 1999. https://bram.org/ident/irc2.htm

Chu, Andrea Long. 'Females.' Verso, 2019.

Cooper, Dennis. 'The Sluts.' Hachette Books, 2004.

Stermitz, Evelin and Annie Abrahams. "Artistic Textual and Performative Paths in New Media Correlations: An Interview with Annie Abrahams," Hz #14, 2009. https://www.hz-journal.org/n14/stermitz.html.